The Right Manager

As increasing emphasis is put on developing leaders, an often-overlooked aspect is if the employee actually has the right manager for them.

We are living in an enlightened age of management and leadership. In more and more companies, managers are being evaluated on their ability to coach, grow, and develop leaders within their organizations, and there is an ever-growing corpus of literature and material out there to help aid in this pursuit. This evolution of the manager role has put the spotlight on the manager-employee relationship and has elevated its importance.

Yet, despite all of these resources available to improve leadership skills, there is woefully little dedicated to evaluating whether an employee is paired up with the right manager. In fact, the only time the subject of “finding the right boss” comes up is in the context of finding a new job.

“Don’t pick a job. Pick a Boss. Your first boss is the biggest factor in your career success. A boss who doesn’t trust you won’t give you opportunities to grow.”

William Raduchel

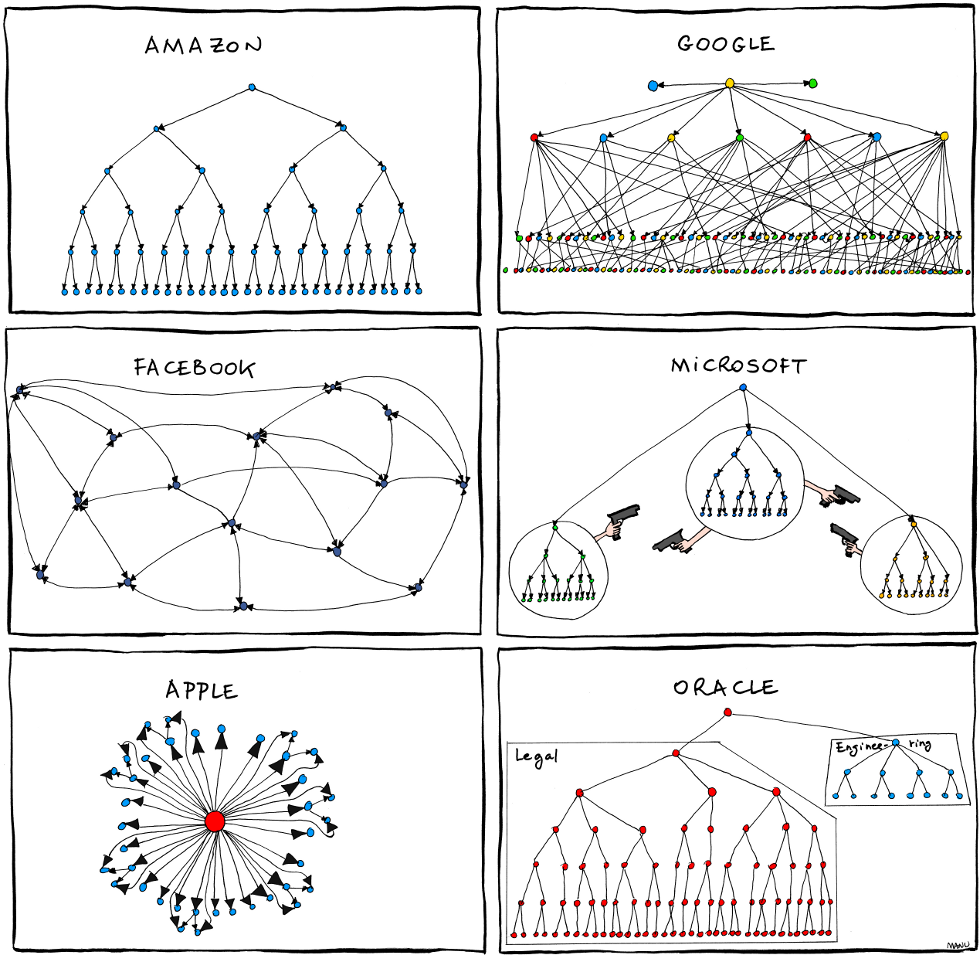

A few years ago, this satirical image circulated the internet, providing some highly simplified insight into how some larger companies deal with their management hierarchies. The original BonkersWorld article has been taken down, but it continues to live on all over the web:

The instant a managerial hierarchy is introduced in a company, the organization has laid the groundwork for what role these managers will play, and the decisions about “who reports to whom” will have cascading effects on the efficacy of the business. For this reason, it is increasingly important for organizations to make very conscious decisions about how they pair their employees with managers. The power, or empowerment, to structure and assign these relationships is a responsibility that should be taken incredibly seriously, and it extends beyond simply having someone with a manager title and budgeted headcount.

Simply put: for organizations to truly recognize and embrace the need to develop their leaders, the heads of these organizations must define and articulate the reasoning behind why certain individuals report into others. These individuals in positions of organizational authority need to be very intentional about balancing the needs of the business with the strength and permanence of the relationship between employees and their managers. The decision to pair an employee with a manager should not simply be a by-product of organizational structure: it should be a deliberate representation of the management ethos across the company.

This post is for those organizational leaders; it describes a non-prescriptive framework that can continually be referenced for new hires, re-orgs, or any other types of manager transitions.

There are four main factors to consider when assigning a manager to a new or existing employee: Alignment around Objectives and Goals, Subject Matter Expertise, Career Progression, and Values. These are not mutually exclusive, and they should be balanced judiciously, as every situation and set of personalities is unique and nuanced. Additionally, this is not just something that needs to be considered for first-line managers and their reports; these factors need to be taken into consideration even for those higher up in the organizational hierarchy, although the motivations behind the decision may be different.

Objectives and Goals Alignment

In many organizations, the primary factor in pairing an employee with their manager is alignment around a particular set of company objectives or goals. If the manager is given a particular area of ownership or is chartered with a particular objective, the entirety of the reporting structure under them will work in support of those goals. The main benefit of this is that it is inherently intuitive for both the manager and the employee: the manager is able to coach and develop their employees while also managing their workload. The danger of over-indexing on this particular factor when assigning a manager is that shifting company priorities may result in the frequent changing of managers or an employee not being able to explore new areas due to a loyalty or attachment to their manager.

Subject Matter Expertise Alignment

For many employees, it is an extremely compelling prospect to be managed by someone who is an expert in their field. This can be incredibly valuable, as this alignment is in direct support of the manager’s responsibilities to train, coach, and mentor those on their team. Assembling a team with this factor as a guiding principle enables team members to learn from not only their manager, but from each other as well. The danger of over-indexing on this factor is that the employee may eventually feel as though they have surpassed the expertise of their manager, or that the employee is not exposed to other potential areas of interest beyond the purview or expertise of their current manager.

Career Progression Alignment

Understanding the career aspirations and growth goals of their employees is a fundamental responsibility of a manager. Because of this, unrelated to the organization’s goals or even the subject matter of the role, an important factor in choosing a manager for an employee is that the manager can coach and mentor their reports in support of their career goals. In many cases, seniority and similar career paths are a consideration; this can help to find common ground relatable experiences. This particular factor is particularly powerful for those employees who have a clear vision for where they want their career to take them. The danger of over-indexing on this particular factor is potentially sacrificing the manager’s connection to the employee’s day-to-day work in favor of focusing on what’s next for the employee.

Values Alignment

Possibly more abstract than the other three factors, “Values Alignment” is about the “human connection” between an employee and their direct report. There are major benefits that come from emphasizing this factor when assigning a manager to an employee, such as the employee’s morale and trust that comes from this safe space and relationship. The danger in over-indexing on this factor, similar to Career Progression, is the potential that the manager has a lack of connection to the employee’s day-to-day work, but also that there could be employee frustrations stemming from the manager’s inability to relate to or understand that work.

Through a combination of these four factors, companies should optimize for the resilience of the ever-important employee-manager relationship through organizational change.

A Balancing Act

One example of a situation that brings all four of these factors into play is represented in a Scrum Team. A scrum team is typically a cross-functional group of individual contributors utilizing their particular specializations and skillsets and working together towards a common goal. In this particular example, Vinay is an engineer on this scrum team, working with 3 other engineers, a designer, two quality engineers, a project manager, and a product manager. Vinay has a great relationship with his manager (a quality that he stated was very important to him when he interviewed, which put more emphasis on Values Alignment), but his manager is unaffiliated with the scrum team, as the team defines their own roadmap and the sprint’s work (usually driven by the product manager). In this case, by downplaying the emphasis on Objectives and Goals Alignment when pairing Vinay with his manager, this gives Vinay the flexibility to work on any projects his team deems important, or even move to other teams.

Vinay is a few years into his career now, and one of the reasons he came to this company was to continue honing his craft — but to also eventually explore moving into management. For this reason, shortly after joining the company, he was assigned to Samantha, an engineering director who had risen through the ranks at a few different companies. Samantha has helped several engineers move into management, and for this reason, there was a clear need to place more of an emphasis on Career Progression Alignment.

Samantha has been in the industry for many years now, and she’s seen technology evolve over the course of her career. However, in the past few years, she has not spent as much time in the code as she once had (or as Vinay is currently, obviously). Fortunately, Vinay is a talented and proactive engineer, learning from his peers (both junior- and senior-level engineers) and finding resources to keep him at the top of his game. For this reason, there was less importance placed on Subject Matter Expertise Alignment when it came to pairing him with Samantha. Had Vinay needed more hands-on help, or he was put in a position where he was working with only other junior engineers, this judgement call may have been different.

In this hypothetical example, some personalized discretion was involved in choosing the right manager for Vinay, and some of the decisions were more driven by the company’s needs and operating model. One possible alternative to this reality would be if Samantha was embedded in Vinay’s (or perhaps another) scrum team as the Scrummaster (as some companies like to do). This would, perhaps, change some of the balance of these factors and the decisions that would go into who the ideal manager should be.

The goal is not to identify the perfect target ratio of these factors for your organization (because there isn’t one). The goal should be to be deliberate and intentional about the decisions you make when it comes to pairing employees and managers.

Selecting a Hiring Manager

The ideal time to talk about choosing a manager is before the hiring process even begins. A well-informed decision at this time has the potential to create a relationship that lasts for many years. Unfortunately, at this point, the information needed to make a decision is strictly one-sided, knowing nothing about the new employee’s perspective (since that potential new person is not even in the hiring pipeline yet). Therefore, the hiring manager (that is, the manager that the new employee will report into) representation on the interview panel is largely based on the company’s or organization’s general philosophy on the first two factors: “Objectives & Goals Alignment” and “Subject Matter Expertise Alignment”. This is where the question needs to be asked: will the organization be best served by hiring someone to report into a manager who shares the same organizational goals, and/or will the organization be best served by hiring someone into a manager who has the same skill-sets? The specific calculus here is dependent on a variety of factors as well, such as seniority desired of the open role. Based on this rough and preliminary assessment, a hiring manager can be chosen. Fortunately, there are safeguards that come in later in case the team optimizes for the wrong thing.

As the interview process commences, more information will come to light around these factors. The hiring manager (and the rest of the interview panel) will have their own specific biases around what they are looking for:

- Is the person interested in working on these types of projects (Objectives & Goals Alignment)?

- Is the person teachable and willing to learn from the hiring manager (Subject Matter Expertise Alignment)?

- What is this person looking to accomplish professionally, and can the hiring manager help with that (Career Progression Alignment)?

- Can the hiring manager establish a personal and trusting relationship with this person (Values Alignment)?

Additionally, the candidates in the pipeline will be similarly evaluating the company’s choice in a hiring manager, possibly unconsciously. They will want to know how they are assigned projects, who in the organization they can learn from, how the company is going to invest in their career growth, and whether they feel like they will be able to have a fulfilling relationship with the hiring manager.

It is important that these internal and external biases are continually explored and acknowledged throughout the interview process. If done diligently, this will help identify and attract the best candidates to the team and ensure the best onboarding experience once they accept.

The First 90 Days

The first 90 days for a new hire should be spent getting to know the individual on a personal level, and Claire Lew’s article on How To Onboard A New Hire lists a ton of great questions that can be used to help with that. Many organizations use these first three months as an evaluation (or even probationary) period for new hires, but frequently overlooked, it is also an opportunity to evaluate the organization’s choice in manager for the new hire.

One strategy that works well for this evaluation is periodic skip-level 1:1s. These meetings between the new employee and their manager’s manager provide a great opportunity to understand how supported the new employee is feeling, what the employee is looking for within the company, and how the manager-employee relationship is developing. These meetings should certainly happen less frequently than the regularly-scheduled 1:1s between the employee and their manager, but should happen 2–3 times over the course of that first 90 days.

The manager-employee relationship is extremely costly to change (from a human relationship perspective), and this is why the 90-day mark is so critical. The employee’s relationship to their manager has the potential to be one of the most impactful and influential relationships that they have in the company. This is the first opportunity to assess if the new employee is appropriately paired with the right manager. If the determination is that the employee is paired up with the wrong manager, this is not an indictment on either the employee or the manager; the choice of hiring manager was made with imperfect and incomplete information.

Manager Transitions

Regardless of what precipitates the idea of a manager transition (whether it be the 90-day evaluation, an ill fit, a manager leaving the company, internal transfers of either the manager or employee, or anything else), a manager change is not something to be dealt with lightly. In the case of an “ill fit” or the employee or manager simply not getting something they want out of the relationship, this can be a valuable coaching opportunity for the manager before any changes are made.

Ultimately though, if the decision is made to change managers, it is important to evaluate the four factors again, but this time with all perspectives properly represented: the company’s, the new prospective manager’s, and the employee’s.

What is the appropriate balance of these four factors that will give the company, the manager, and the employee the best chance for success? If appropriate, directly asking the employee for their perspective can yield positive results, such as hearing if there’s someone specific in the company they’d like the opportunity to report into. Discussing the reasons behind that can be both insightful and introspective, although not necessarily determining.

Any change in reporting structure should be done thoughtfully, infrequently, and consensually.

Once a new manager is identified, the change should be handled delicately. If possible, this should be handled personally by either the current manager or the manager’s manager, as is situationally-appropriate. The person addressing this change should handle the situation with empathy and be prepared to listen for any feedback or concerns that the employee has. A follow-up meeting can be scheduled with the employee, the previous manager, and the new manager to ease the transition by sharing any background and career development plans, and also provide room for questions. The two managers may have different styles, different areas of ownership, or different values, and these are all open for discussion.

On a personal note, one of the best managers I have had told me that management is a lifelong commitment, and that if I was not growing under his leadership, he took it as his personal responsibility to help me find something else, within or outside of the company.

It is critically important that companies devote the same time, attention, and energy into the employee-manager relationship as they do in hiring. The ability to coach, develop, and retain new leaders is directly related to how well and how deliberately companies are able to align managers and their team members.